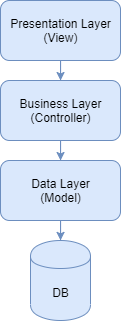

class: center, middle # Code and architecture principles --- ## Summary .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a>] Learn about some basic principles that will help you write cleaner, more organised code This material is part of the [Géoinformatique opérationnelle : Développement avancé d’outils](https://github.com/Tazaf/heig-mdt-gio1) for the [Master of Science HES-SO en Développement Territoriel](https://master.hes-so.ch/domaines/ia/mdt). --- ## Getting started .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a>] Writing code can be **hard**. You have to: - Know the **language** you're writing with - Know how and if it can do what you want it to - Write the code without **syntax** errors - Write code **without nasty bugs** - ... Thus, beginner programmers could write code while only caring about the end result (a program without bugs that does what it's supposed to), without thinking about **how they actually write the code** itself. This often results in [**Spaghetti Code**][spaghetti-code] ; a code that has **no structure** and is **hard to read, understand, fix and maintain**. We'll see in this course the **basic principles that you should always have in the back of your mind** when writing code. > Please note that all future code illustrations will use JavaScript --- ## D.R.Y. .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a>] This first principle is an acronym _(many of those principles are)_ that means: [**D**on't **R**epeat **Y**ourself][d.r.y.] The meaning is quite obvious: **you should not repeat the same piece of logic twice in your program**. If you find yourself copy/pasting or writing the same line(s) more than one time, then you might want to ask yourself if this couldn't be **extracted in a shareable program unit**. In JavaScript (and many other langauges), this unit usually is a **function** (or a class). > The anti-principle of _D.R.Y._ is _W.E.T._, as in "**W**rite **E**verything **T**wice". --- ### _W.E.T._ Illustration .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a> > <a href="#4">D.R.Y.</a>] Let's illustrate that with a simple script that extracts the initials out of a person's name. ```js // This value could come from any kind of user input const name = "Mathias Oberson"; // Create an array of strings by spliting the name at each space const parts = name.split(" "); // Get the first letter of the first part in upper case followed by a dot const firstInitial = parts[0].charAt(0).toUpperCase() + "."; // Get the first letter of the second part in upper case followed by a dot const secondInitial = parts[1].charAt(0).toUpperCase() + "."; // Concatenate both initials const initials = firstInitial + secondInitial; console.log(initials); // Prints: M.O. ``` > What's not D.R.Y. about this code? --- #### Explanation .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a> > <a href="#4">D.R.Y.</a> > <a href="#5">_W.E.T._ Illustration</a>] The main issue with this code is the fact that we wrote twice the logic to **extract the initial off of a name's part**. This is not a very complex logic, and it's only one line of code, so why bother?! - Copy/pasting (or rewriting) it every time we want to use it increases significantly the risk of making a mistake (forgetting the final dot, messing up with the indexes, ...). - If the requirements change and initials should now be in lower case, you'll have to replace `toUpperCase()` with `toLowerCase()` everywhere you pasted the snippet of code > And don't even think about using your IDE's search & replace feature... `toUpperCase()` is probably used in many unrelated places - Plus, reading a line like `parts[0].charAt(0).toUpperCase() + "."` does not instantly make you think: "A'ight! That's an initial extraction". So, let's rewrite some of this code by extracting the repeated line in its own function. --- #### D.R.Y.er code .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a> > <a href="#4">D.R.Y.</a> > <a href="#5">_W.E.T._ Illustration</a>] ```js const name = "Mathias Oberson"; const parts = name.split(" "); const firstInitial = `extractInitial(parts[0])`; const secondInitial = `extractInitial(parts[1])`; const initials = firstInitial + secondInitial; console.log(initials); *function extractInitial(word) { * return word.charAt(0).toUpperCase() + "."; *} ``` The code is now: - **More readable**: the function name `extractInitial` is clear enough so we understand what it does - **More maintainable**: only one place to modify, if the initial extraction process ever changed --- #### Ultimate D.R.Y. .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a> > <a href="#4">D.R.Y.</a> > <a href="#5">_W.E.T._ Illustration</a>] But we could by D.R.Y.er again! - The call to `extractInitial` is written twice. That's not an issue _per se_, but since `parts` is an `array` we should write our code to loop through it - The overall logic (splitting the name, extracting and concatenating initials) will probably be repeated whenever we need initials from a name Let's rewrite our code again: ```js const name = "Mathias Oberson"; console.log(getInitialsFromName(name)); function getInitialsFromName(name) { const parts = name.split(" "); // Split the name let result = ""; // Initialize the final result for (const part of parts) { // Loop through each part of the name result += extractInitial(part); // Concatenate the current part's initial } return result; } function extractInitial(word) { return word.charAt(0).toUpperCase() + "."; } ``` --- ### Pitfalls and dangers of overD.R.Y.ing .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a> > <a href="#4">D.R.Y.</a>] - D.R.Y. is **not** about preventing the repetition of **code**, but rather the repetition of **logic** Repeating the same line of code twice might be perfectly OK if this repetition is done in different **contexts or features** - Trying too hard to D.R.Y. your code will probably lead to **higher complexity**, due to unnecessary abstractions or premature refactoring You should avoid applying the D.R.Y. principle when it's not necessary ("just in case"). > Following the D.R.Y. principle should always be balanced with **code simplicity** and only implementing what's **currently necessary**, both of which are explored later on this slidedoc. --- ## K.I.S.S. .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a>] The second principle we're going to see is K.I.S.S., that stands for [**K**eep **I**t **S**tupid **S**imple][k.i.s.s.] The idea behind this principle is quite simple itself: **don't make things needlessly complicated**. Although short, this idea requires a little bit of details... --- ### The Art of Naming .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a> > <a href="#10">K.I.S.S.</a>] A very basic way to write K.I.S.S. code is to allow yourself some time to think about pertinent names for your variables, constants, functions, classes, etc. You could be tempted to just name them `a`, `b`, `c`, `p1`, `fun`, etc. because you just want to get things done. That's a **wrong trade off**. Read the same script **the day after** you wrote it, and track how many minutes you're **losing** trying to remember what this `ccu` variable represents. Nowadays, all IDEs and text editor helps you reference existing symbols in your code to prevent typos, so the length of their name doesn't really matter. **Be descriptive!**\* If your variable is supposed to contain an object representing the currently connected user, then call it `currentlyConnectedUser`, or `currentUser`. > (\*) Don't fall into the opposite habit, though, going the Java way and starting naming your classes `AbstractFlushClearCacheMessageBuilderOnTransactionSupport` because that's the most descriptive you can get... --- ### Do not write code to show off... .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a> > <a href="#10">K.I.S.S.</a>] Whenever possible, always favor the **readability** of your code over its cleverness. Some people takes pride in writing very short pieces of code that are very ingenious but will require other developers to **pause for a minute or two** _(if not more)_ to understand them, **each time they encounter them**. Here's an example for the ["Fizz/Buzz"][fizzbuzz] problem: ```js for (i = 0; ++i < 101; console.log(i % 5 ? f || i : f + "Buzz")) f = i % 3 ? "" : "Fizz"; ``` > It does the job, uses some obscure clever mechanism of the `for` loop, but is a mess to read, understand and debug... --- ### ...aim at readability... .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a> > <a href="#10">K.I.S.S.</a>] Unless those clever pieces of code are absolutely necessary _(which they probably aren't)_, then you'd be better off **writing a few more lines** instead to make sure **the logic is more comprehensible** (by others and also yourself). Here's another solution to the "Fizz/Buzz" problem: ```js for (let nb = 1; nb <= 100; nb++) { const mod3 = nb % 3 ? "" : "Fizz"; const mod5 = nb % 5 ? "" : "Buzz"; console.log(mod3 || mod5 ? \`${mod3}${mod5}` : nb); } ``` There's a few more lines, but the structure and the logic are **way more obvious**. --- ### ...to a certain extent .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a> > <a href="#10">K.I.S.S.</a>] - Do not refrain yourself from **using language specific features** by fear of others not being able to understand them: if people don't know them, they will **learn** the first time they encounter them, and understand them thereafter. - Also **don't sacrifice performance** over readability. You can write performant code while still being comprehensible for programmer with general knowledge of the used language. - At the very least, if you think a bunch of lines you wrote are necessary to your application, but could be a little be to complicated for your fellow developpers, **explain them by commenting them!** --- ### Take a step back .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a> > <a href="#10">K.I.S.S.</a>] In general, to apply this K.I.S.S. principle, you should as often as possible **take a step back** on what you just wrote or designed and ask yourself if all of this **could not be simplified**, stripped down to its basics without sacrifices for the feature. > Taking the time to **think about the design** of your application code and structure will help you in the long run, when debugging, maintening or adding features to it. - Isn't there a **library** out there that already does what I'm trying to implement? _(the less code you type, the less issue you'll create)_ - Doesn't the language I use offer some **native behavior** for what I'm trying to do? _(don't reinvent the wheel)_ - Do I really need **all those classes/functions** in my code? _(too much of them will make your application harder to grasp)_ And if you find yourself changing or modifying your code, **don't hesitate to delete unused code**. With source control tools like Git, you'll be able to **come back to it** if needed, and it will not **bloat** your code base _(other won't ask themselves when it's used or what it does)_. --- ## Y.A.G.N.I. .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a>] The third principle to keep in minde is Y.A.G.N.I., which stands for [**Y**ou **A**ren't **G**onna **N**eed **I**t][y.a.g.n.i.] The basis of this principle states that **you should not implement features and functionnality based on their assumed usefullness in the future, but because they are necessary at the time**. You still should **design** your code so that it **could** easily be **extended or enhanced** in the future ; by properly using functions, classes, interfaces, and other mechanisms provided by the language you're using _(remember to still K.I.S.S., though)_. But you should **not actually code more** than what you need at present, even if you're 100% sure that this will come in handy in a not-so-distant future. --- ### You can not predicte the future .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a> > <a href="#16">Y.A.G.N.I.</a>] Let's suppose that **you did develop an feature** that is not a current requirement, but you're sure it will soon be. - It might happen that the feature you foresaw actually needs to be implemented. It will **probably not** have the exact same requirements you **thought it would**, and you have to modify the code you previously wrote to match the actual requirements of the feature. If you're lucky, it will only be minor changes ; more often than not, it will be **a complete refactoring**. The time you took in the past to implement the feature has been wasted. - It might also happen that **the code you wrote is never ever used**... you'll then have a code base with unused code. You'll probably forget that it's not used and keep maintaining, optimizing and/or testing it. --- ## S.R.P. .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a>] This principle is related to how you should design and architecture your code. It means: [**S**ingle **R**esponsibility **P**rinciple][s.r.p.] The basic definition of this principle states that **a program unit (function, class, etc) should only be responsible of doing one thing**. Let's take an example of a feature we'd want to implement in an app: **"Display markers on a map, based on data retrieved from a webservice"** On the next slide, I propose a pseudo-implementation for this feature. > Note that this example is in **pseudo-code**. It won't work if executed, event if it looks like valid JS. --- ### Omnipotent function (1/2) .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a> > <a href="#18">S.R.P.</a>] ```js function displayMarkerOnMapFromWebService() { let markersData; let markers = []; const request = new XMLHttpRequest(); request.open("GET", "https://geo.dummy-service.ch/markers"); request.send(); request.onload = () => { if (request.status === 200) { markersData = JSON.parse(request.response); } markersData.forEach((markerData) => { const marker = new Marker(); marker.name = markerData.name; marker.coordinates = { lat: markerData.latitude, long: markerData.longitude }; markers.push(marker); }); const map = new Map("map"); markers.forEach((marker) => { map.addMarker(marker); }); map.displayMarkers(); }; } ``` --- ### Omnipotent function (2/2) .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a> > <a href="#18">S.R.P.</a>] Now we have a function that **does everything**: fetch the data from the webservice, create the markers from it, add those marker on the map to display them. It doesn't follow the S.R.P., since it is **directly** responsible of executing all those actions. But this `displayMarkerOnMapFromWebService` function should not care about **how** those actions are performed ; that's not its responsibility. It should only care about the **overhall logic of the process**: ```js function displayMarkerOnMapFromWebService() { // Call webservice to get raw data getDataFromWebService((markersData) => { // Create actual markers const markers = createMarkersFromData(markersData); // Give them to the map for display displayMarkersOnMap(markers); }); } ``` Each new function called by `displayMarkerOnMapFromWebService` is responsible for carrying out one action. --- ### Why? .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a> > <a href="#18">S.R.P.</a>] - Ensuring as much as possible that every function is responsible of one task will allow you to have **a clear model of how the application works**. - It also helps in **writing reusable code** ; you can more easily build a complex logic out of small independant parts than with omnipotent functions like the initial example. - If there's an **issue** with one of the actions, you know exactly **where to look**. - Should any of those actions' **implementation changes**, you can safely **modify the corresponding function** without having to alter the others. > Note that, although we only mention functions here, the S.R.P. can be applied to any aspects of the code. --- ## S.O.C. .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a>] The last principle we'll see is a continuation of the previous one, and means [**S**eparation **O**f **C**oncerns][soc] If the Single Responsibility Principle is generally related to how **the low level code is structured** (the small building blocks of a program like functions or classes), the SOC principle is more related to how your **application is architectured**. Let's **look at a web application**, for illustration. The first thing you'll notice as a user is **its user interface**. When you use this interface to perform actions (such as submitting a form), the application will probably **validate** its content, **do something** with it then **save** whatever the result in a permanent way, most likely in a database of some sort. This web application will have code somewhere in its code base to perform all those actions. --- ### Separate and regroup .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a> > <a href="#22">S.O.C.</a>] Since you now know about the S.R.P., you know that those tasks should be carried out by **separate program unit** (functions, methods, classes, etc). But querying a database, applying business logic and generating a complete user interface would **require many, many different units**. Grouping all **those units in a single place** would not be a good idea, much like it was not a good idea to have one function to do everything. You will need to **separate and group them based on what they do**: - All the units that are related to generating or managing a user interface should be grouped together. - Same goes for all the units related to managing the data model. - The program unit related to the business logic should also be grouped together. > Those groups of related program unit represents the **layers** of an application. --- ### Layers .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a> > <a href="#22">S.O.C.</a>] The layers are an **abstract representation** of how an application is architectured, at an higher level. **It's abstract because the actual application source code files will not necessarily be organised in the same way** .grid-50[ > The previous example with a layer for the user interface, one for the business logic and another for the data, is very similar to a common **architectural pattern** known as MVC ([**M**odel - **V**iew - **C**ontroller][mvc]), used by many web framework such as Laravel, Spring, Ruby on Rails, etc. ] .grid-50[  ] --- ### Modularization .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a> > <a href="#22">S.O.C.</a>] How you can group your program unit together is higly dependant on the language your using. - in PHP, you have the **namespace** mechanism to organise your classes in a hierarchical structure - in Java, you have **packages** to achieve the same purpose - in Python and JavaScript, you have the **modules** mechanism (which is what we'll dig into later) Using any of those mechanism allows you to **design your application** following the S.O.P. principle. The **benefits** of doing so are very much the same than for the S.R.P., although to the **application level**, more than the code level. --- ## Resources .breadcrumbs[<a href="#1">Code and architecture principles</a>] - [The D.R.Y. Principle: Benefits and Costs with Examples][d.r.y.-in-depth] - In-depth analysis of the D.R.Y. principle - [A Detailed Explanation of The K.I.S.S. Principle in Software][k.i.s.s.-in-depth] - In-depth analysis of the K.I.S.S. principle (with a little bit of Y.A.G.N.I. inside) - [The Single Responsibility Principle Revisited][s.r.p.-in-depth]: In-depth analysis of the S.R.P. - [Principles To Code By][principles-article] - Overview of coding principles, applied to an example [spaghetti-code]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spaghetti_code [d.r.y.]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Don%27t_repeat_yourself [d.r.y.-in-depth]: https://thevaluable.dev/D.R.Y.-principle-cost-benefit-example/ [principles-article]: https://medium.com/dailyjs/principles-to-code-by-3c516ad61fcc [k.i.s.s.]: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Principe_K.I.S.S. [fizzbuzz]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fizz_buzz [k.i.s.s.-in-depth]: https://thevaluable.dev/k.i.s.s.-principle-explained/ [y.a.g.n.i.]: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Y.A.G.N.I. [s.r.p.]: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Principe_de_responsabilit%C3%A9_unique [s.r.p.-in-depth]: https://thevaluable.dev/single-responsibility-principle-revisited/ [soc]: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/S%C3%A9paration_des_pr%C3%A9occupations [mvc]: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mod%C3%A8le-vue-contr%C3%B4leur